Introduction to Next Generation Sequencing

Posted on June 2, 2021 • 3 minutes • 598 words

It was a tough time to choose a topic for this blog. For, I wanted to write about a common topic, evolving at a faster rate, yet less known and is a must-read for every biologist. This is the genesis for today’s topic: “Next Generation Sequencing”. Most of us might have heard about it, few have already read about it, and a few must also have performed it. My target audiences here are those who want a bird’s eye view on different generations of sequencing technologies, giving you a base knowledge to explore more about this magical innovation.

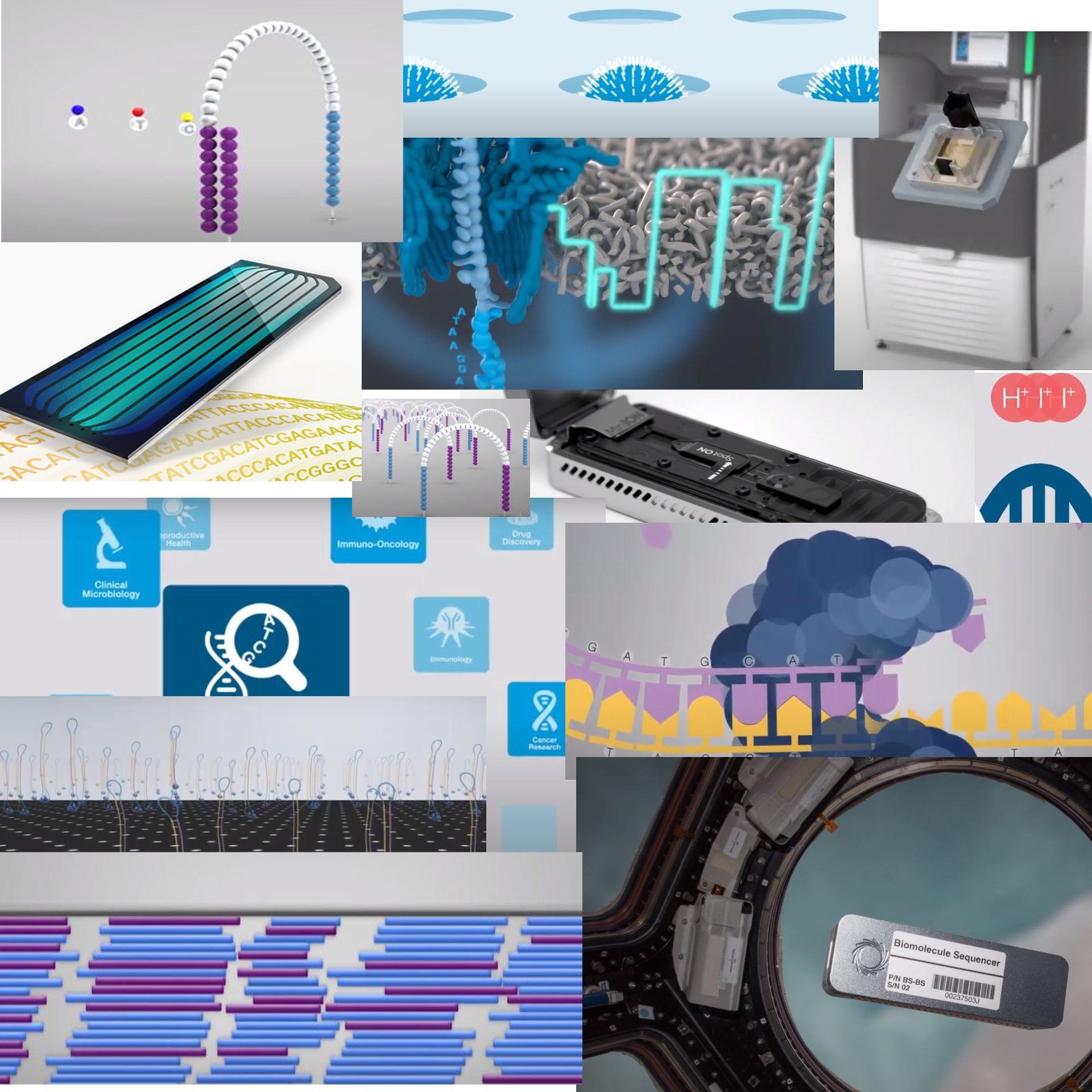

Broadly, I shall divide the technologies into two parts: Short-read (DNA immobilization), and long-read (Protein Immobilization) technologies. And yes, the blog post is still targeted to a layman even after the usage of these jargons. So this is the story. The source code of a living organism has four different letters, and it lies in our genes which are very long. The sequencing technologies take the genes and reads the sequence and gives an output in a digital format of four letters: A, G, T, C.

##Short read Technologies

As seen above, several long genes are broken into smaller pieces and are later assembled to form the original sequence. One of the easiest ways to identify these letters is by copying them. An enzyme called DNA polymerase stitches different letters present in the mixture exactly complementary to the fragmented genes. When we provide the enzyme only a single letter and if it is complementary; the Polymerase chains it to the replicating unit. This process can leave different kinds of signatures–one of the signals being a Proton (Used by Ion Torrent). If a signal is received by the addition of a specific letter, it would indicate that the letter is being copied, and a different letter is sent the next time.

Often letters are fused with a light-producing molecule (as in Roche 454) which is cleaved when it gets copied to the current template. The presence of the same letter more than once (homopolymers) increases the signal strength, but it gets saturated after a few continuous repeats. Illumina technology uses letters that block the replication process. Another reaction must be carried out to remove the blocking groups, and then the replication proceeds.

In all these methods, the gene is immobilized on: solid-state flow cell (Illumina), bead-based (454 & Ion torrent)–uses emulsion PCR. Therefore, it is easier to monitor the signals when small fragments are used, restricting us to short reads.

##Long read Technologies

Intuitively, immobilizing the enzyme which copies the genes and providing different letters each giving different colours of lights is an easier way to read the sequence. Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) technology does the same process reading a maximum of 40,000 letters at a single stretch. But this approach only gives 87% accuracy at a single pass. The reason could be that the polymerase enzyme fused in a transparent well tends to give errors and has lesser fidelity compared to our need. Overcoming this inherent limitation, Oxford Nanopore technology uses an immobilized motor protein that sends a single DNA strand (from the gene) into a small protein pore (Nanopore) which is passed through a constant ionic current. The moment the gene moves through the pore, each letter creates a characteristic disturbance in current. These disturbances can be translated to read the letters. Oxford Nanopore used to have an error rate of around 30%, but now the Nanopore reads the sequence with 95-98% accuracy. These are small portable machines that can read a maximum of 900,000 letters at a single stretch.