All about Diabetes

Posted on December 3, 2025 • 5 minutes • 1010 words

The dangers of diabetes, the daunting medical costs, and its further medical implications are something that many are well aware of. Some of you might pride yourself in being more aware of the mechanisms of diabetes, and some might barely have an idea. Whatever category you belong to, your curious explorer challenges you today. I welcome you to seek the knowledge that could maybe empower you, or even make you healthier. This is the one place you need to go to get a wholesome understanding of Type-2 Diabetes, where I talk and explore the theoretical concepts and practical data supporting it. Join me in this exploration of a better lifestyle.

If a sentence looks technical, you can skim the darker-green passages, which highlight more jargon-heavy explanations.

When people refer to diabetes — particularly type 2 — they are often describing progressive dysfunction of the pancreatic beta cells. These cells produce insulin, and when they fail, blood glucose rises. Several processes contribute to beta-cell decline. Some important contributors include islet amyloid polypeptide (IAAP) deposition, chronic low-grade inflammation, and genetic factors that predispose individuals to beta-cell dysfunction.

Among these contributors, one area that has received considerable attention is glucolipotoxicity, a term that captures the combined damaging effects of elevated glucose and elevated fatty acids on the beta cells.

Glucotoxicity describes the damaging effects of prolonged high glucose, which can trigger oxidative stress through the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Lipotoxicity, by contrast, results from accumulation of harmful lipid intermediates —for example, ceramides and diacylglycerols that can build up when free fatty acids rise.

While lipotoxicity has its own damaging pathway, what is often underappreciated is that glucotoxicity can drive lipotoxicity. Prolonged high glucose can enhance fatty acid release from adipocytes, promoting the buildup of these toxic lipid compounds. For that reason, glucotoxicity is often the more upstream and impactful initiator of beta-cell stress.

Elevated blood glucose is harmful, and the body normally uses multiple mechanisms to control it. When glucose rises, insulin is released; insulin signals tissues to take up glucose and use it. If blood glucose stays high for long periods, the body produces more insulin, and tissues can become less responsive — a state known as insulin resistance (IR). Insulin resistance is an early and common hallmark of type 2 diabetes: higher IR means poorer glucose uptake and higher blood glucose levels.

A closer look at signaling pathways shows how repeated glucose exposure can induce IR. Chronic hyperglycemia can promote inhibitory serine/threonine phosphorylation of IRS proteins, sustained mTORC1 activation, and increased PTEN expression in adipocytes — all of which blunt Akt signaling and impair glucose uptake.

From a broader perspective, the logic becomes straightforward: more frequent or higher glucose spikes increase the chances of developing insulin resistance. As resistance builds, glucose remains elevated for longer, placing additional stress on the beta cells. Over time, this vicious cycle accelerates their decline. The mechanism above is one of several paths to beta-cell failure. IAAP depositions and chronic inflammation can damage beta cells; reduced hepatic clearance of insulin can contribute to hyperinsulinemia; and pathways such as the polyol pathway, the hexosamine pathway, and formation of advanced glycation end-products also matter, often interacting with genetic susceptibility. Genetics still provides a major underlying influence, but environmental factors — and especially glucose exposure — can affect how quickly dysfunction progresses.

No single definitive trial proves that flattening glucose spikes prevents diabetes, but multiple studies suggest that reducing prolonged glucose exposure can slow progression in high-risk people. For example, acarbose — an α‑glucosidase inhibitor that slows carbohydrate digestion — flattens post-meal glucose curves and delayed diabetes onset in people with impaired glucose tolerance.

Similarly, the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study showed that lifestyle changes reduced the incidence of type 2 diabetes by roughly 25% on average. These findings do not negate the dominant role of genetics, but they reinforce the idea that limiting glucose excursions is one of the few modifiable levers we have.

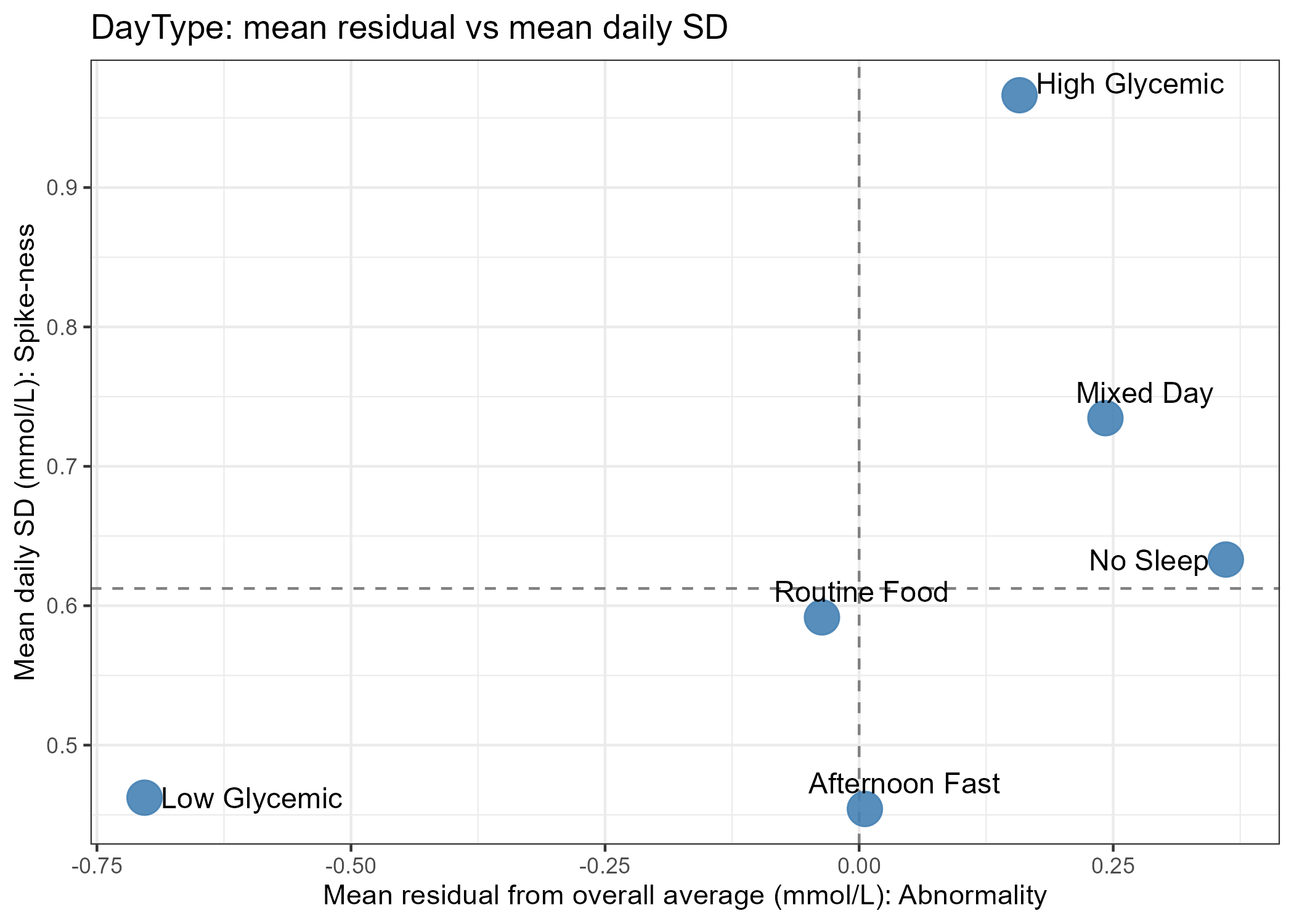

Because lifestyle is modifiable while genetics is not, I decided to explore how daily habits shaped my glucose responses. I used a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) — a Freestyle Libre sensor I accessed through my brother Praveen — to record data across many days.

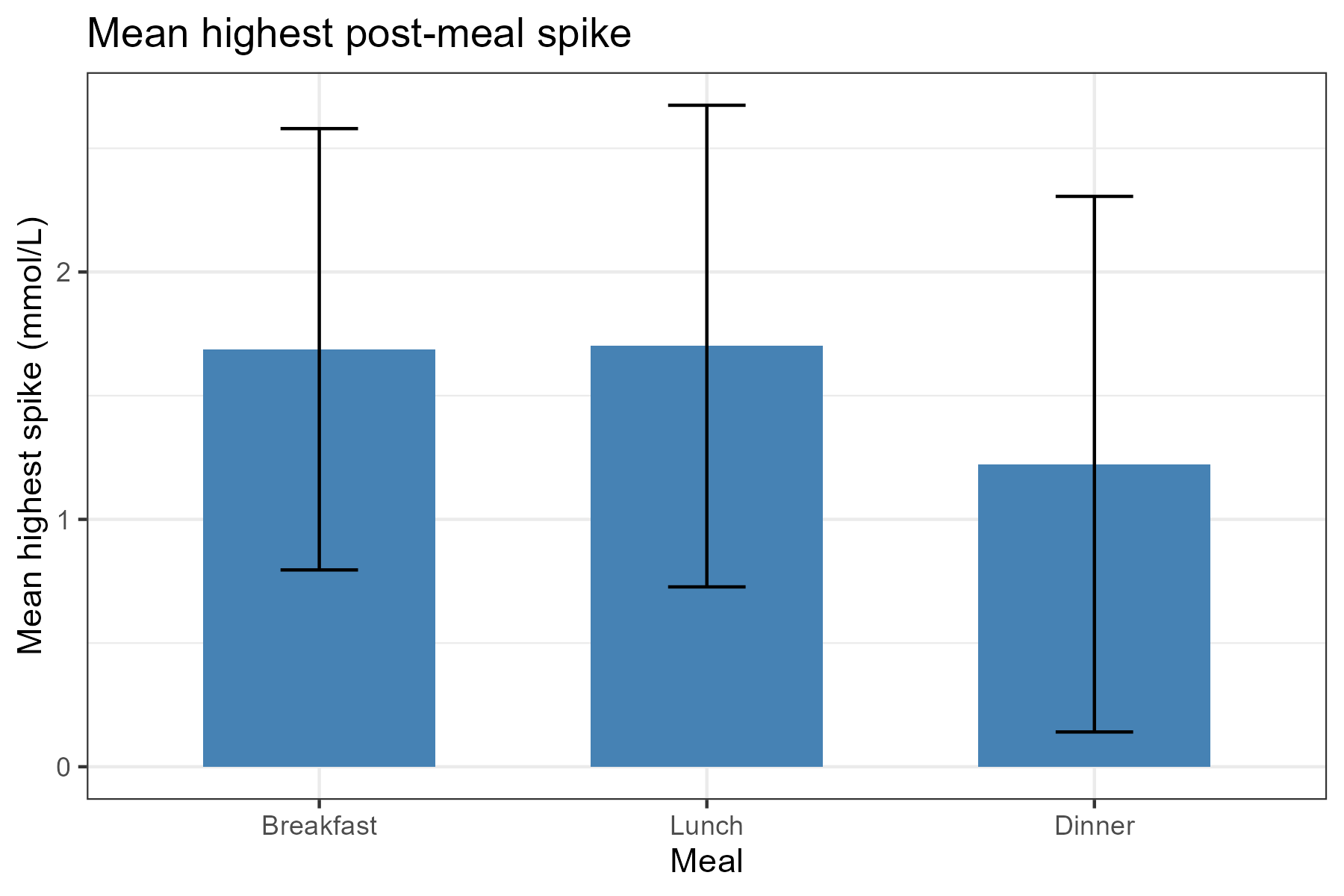

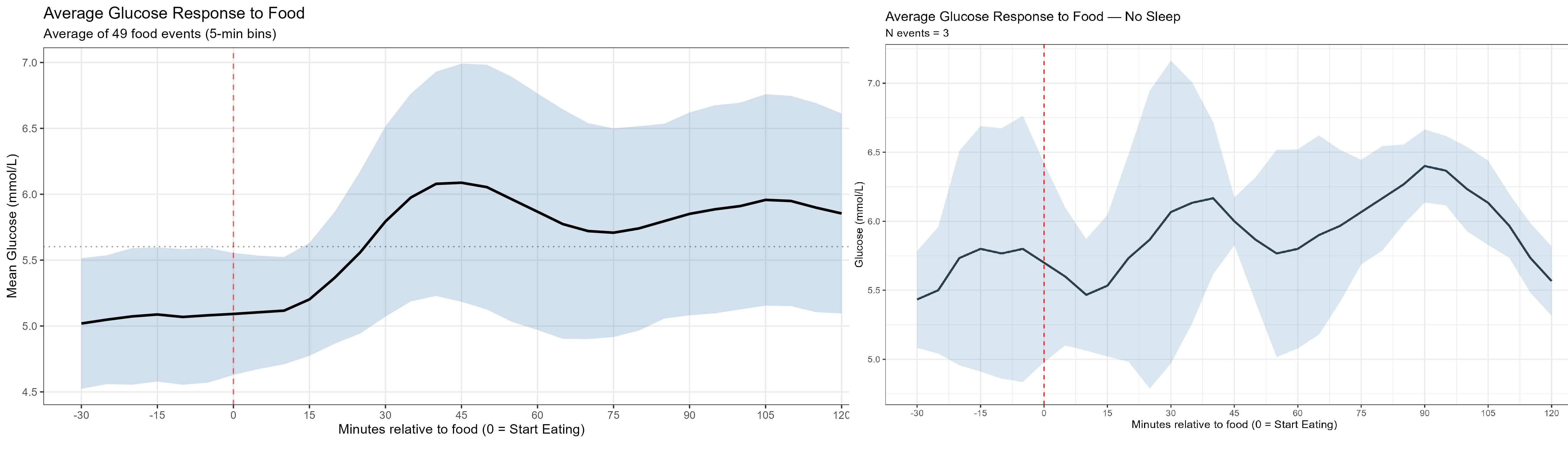

Using the CGM, I tracked how diet, exercise, sleep, and stress affected glucose. In my recordings, glucose typically peaked around 60 minutes after eating, after which insulin action pulled levels back down.

One clear pattern was the effect of physical activity on the glucose curve. Morning spikes are often higher because of hormonal factors, but on days I jogged before breakfast and skated to work, spikes were much lower. When I skipped exercise, spikes were clearly higher. The difference could be striking.

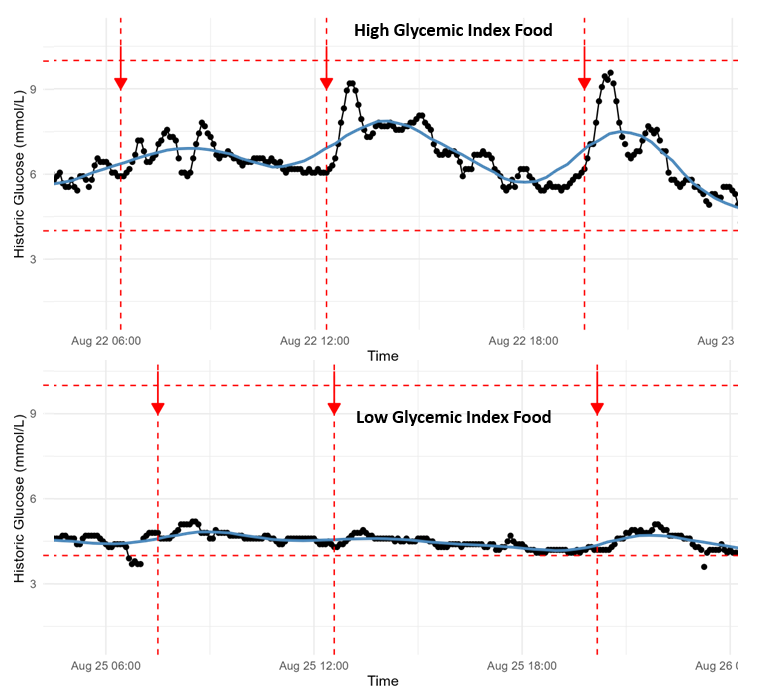

Dietary patterns produced visible differences as well. Low‑glycemic meals — salads, higher-protein or lower‑carbohydrate combinations — gave flatter curves, while high‑glycemic meals produced steeper spikes. Foods like bananas, chocolate, potatoes, or sugar-rich meals led to substantially larger spikes than baseline.

Sleep and stress were major variables. After skipping a night of sleep to simulate stress, my glucose pattern became the most erratic I recorded: glucose rose faster (peaking around 30 minutes instead of ~60) and the day showed many more spikes. This highlighted how sensitive glucose regulation is to sleep deprivation and stress.

I also tested food temperature, fasting intervals, mixing low‑ and high‑GI items, and other small, low-cost hacks to reduce peak heights with minimal routine changes. Each intervention produced different effects: adding ghee (clarified butter), refrigerating food, or adding pickles sometimes produced noticeable changes, while toasting bread or adding cheese/veggies to pasta often had little or subtle impact.

If you want the specifics or to try these analyses yourself, my data analysis code is on GitHub: GlucoMeterReadings_analysis (code & analysis) . This project grew from curiosity about how daily choices affect glucose exposure and, by extension, beta‑cell stress.

While lifestyle changes cannot override genetics, they can meaningfully influence the environment in which our beta cells operate. This blog post is a nod to all the people who try to fight fate and improve their lifestyle.